ESA

It has now been two weeks since the targeted launch of the European Space Agency’s €1.5 billion probe to the moons of Jupiter.

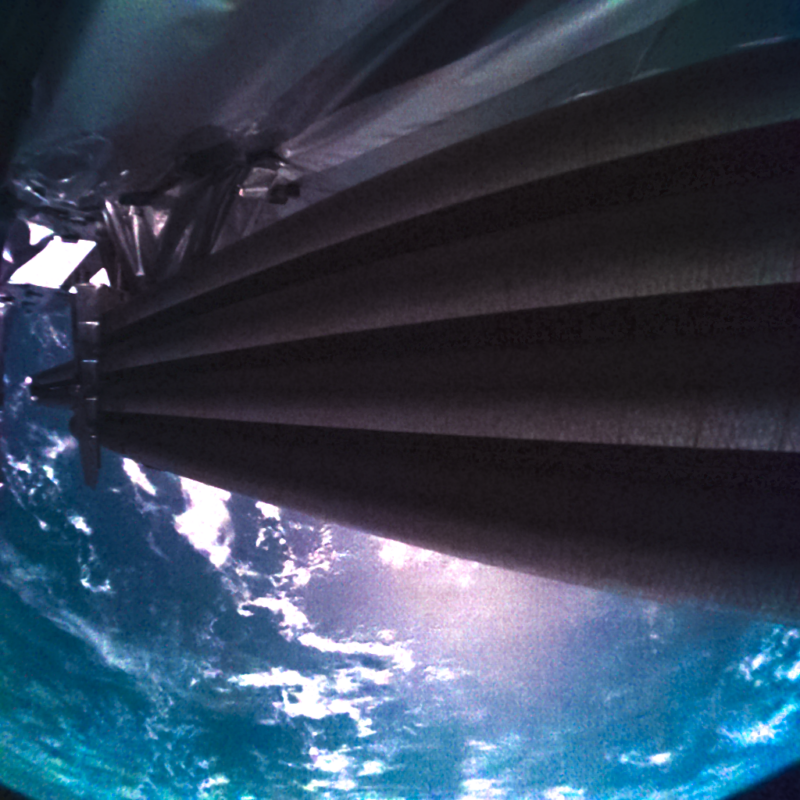

This process was going well until the space agency tried to extend a 16-meter antenna that is part of its radar. The Radar for Icy Moon Exploration, or RIME, is an important science tool on the spacecraft because its ground-penetrating radar will allow the interiors of interesting moons like Europa and Ganymede to be examined.

On Friday, and European Space Agency said The long antenna remains stuck into its mounting bracket and is only extended to about a third of its full length. Engineers at the spacecraft’s Mission Control Center in Darmstadt, Germany, are working on the problem.

“The main current hypothesis is that a small stuck pin has not yet given way to release the antenna. In this case, it is thought that just a few millimeters can make the difference to set the rest of the radar free.” He said. “Various options are still available to push the critical instrument away from its current location. The next steps to fully deploy the antenna include a burn in the motor to rock the spacecraft a bit, followed by a series of spins that will turn the juice, heating Mount and Radar, which are currently in the cold shadows.”

With so many options for unscrewing the antenna and nearly eight years of travel before Juice reached the Jovian system, Europe probably has a good chance of solving this problem.

It’s also worth noting that the rest of the Juice spacecraft is healthy, and the rest of the run has gone smoothly. However, while this antenna is not very important and there are plenty of other science instruments on board, it is one of the most important.

The issue is reminiscent of the difficulty NASA had in deploying the high-gain antenna on the Galileo spacecraft, which blasted off to Jupiter in 1989 on the space shuttle. This antenna, required for high-speed communications between spacecraft and Earth, remained only partially deployed after years of efforts to solve the problem. NASA eventually had to use a lower-gain antenna, which resulted in a much slower rate of data than Galileo’s.

“Reader. Infuriatingly humble coffee enthusiast. Future teen idol. Tv nerd. Explorer. Organizer. Twitter aficionado. Evil music fanatic.”