In a self-described “thought experiment,” University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank and colleagues David Grinspoon at the Planetary Science Institute and Sarah Walker at Arizona State University used scientific theory and broader questions about how life might change the planet, to postulate a four-stage description of Earth’s past and possible future. Credit: University of Rochester Photography/Michael Osadio

Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank discusses why cognitive activism operating on a planetary scale is important to address global issues such as climate change.

The collective activity of life – all microbes, plants and animals – has changed the planet.

Take, for example, plants: plants “invented” a way to undergo photosynthesis to enhance their survival, but in doing so released oxygen that completely changed the function of our planet. This is just one example of individual life forms that perform their own tasks, but collectively influence on a planetary scale.

If the collective activity of life – known as the biosphere – can change the world, can the collective activity of cognition, and action based on that cognition, also change the planet? Once the biosphere developed, the Earth took on a life of its own. If a planet with a life has a life of its own, does it also have a mind of its own?

These are the questions that Adam Frank, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Rochester, asked Adam Frank, Fred H. Gwen, colleagues David Grinspoon at the Planetary Science Institute, and Sarah Walker at Arizona State University, in a paper published. In the International Journal of Astrobiology. Their self-described “thought experiment” combines current scientific understanding about Earth with broader questions about how life might change a planet. In the paper, the researchers discuss what they call “planetary intelligence” – the idea of cognitive activity operating on a planetary scale – to spark new ideas about ways in which humans can tackle global issues such as climate change.

As Frank says, “If we ever hope to survive as a species, we must use our intelligence for the greater good of the planet.”

An immature technosphere

Frank, Grinspoon, and Walker extract ideas such as the Gaia hypothesis—which proposes that the biosphere interacts vigorously with the nonliving geologic systems of air, water, and land to maintain the Earth’s habitable state—to explain that even non-technologically capable species can display planetary intelligence. The key is that the collective activity of life creates a self-sustaining system.

For example, says Frank, several recent studies have shown how tree roots in the forest are connected via underground networks of fungi known as mycorrhizal networks. If one part of the forest needs nutrients, the other parts send the stressed parts the nutrients they need to survive, through the mycorrhizal network. In this way, the forest maintains its viability.

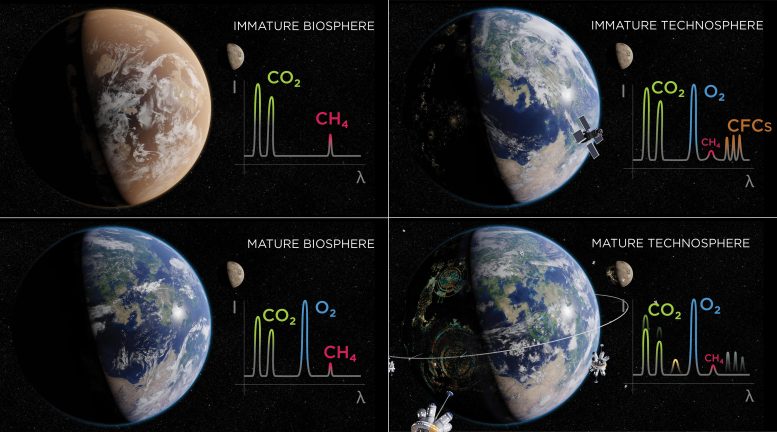

The researchers hypothesized four phases of Earth’s past and potential future to illustrate how planetary intelligence could play a role in humanity’s long-term future. Currently, the Earth is considered an “immature technical area” because the majority of energy and technology use involves the degradation of Earth’s systems, such as the atmosphere. To survive as a species, we must aim to be a “mature technology field,” says University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank, with technological systems that benefit the entire planet. Credit: University of Rochester Photography/Michael Osadio

Right now, our civilization is what researchers call the “immature technosphere,” an assemblage of human-generated systems and technology that directly affect the planet but are not self-sustaining. For example, the majority of our energy uses include the consumption of fossil fuels that degrade Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. The technology and energy we consume to survive is destroying our home planet, which in turn will destroy our human race.

To survive as a species, we need to act collectively for the good of the planet.

But, Frank says, “we don’t yet have the ability to collectively respond to the planet’s best interests. There is intelligence on Earth, but there is no planetary intelligence.”

Towards a mature technosphere

The researchers hypothesized four phases of Earth’s past and potential future to illustrate how planetary intelligence could play a role in humanity’s long-term future. They also demonstrate how these stages of development driven by planetary intelligence may be characteristic of any planet in the galaxy developing life and a sustainable technological civilization.

- Stage 1 – the immature biosphere: a feature of the very early Earth, billions of years ago and before technological species, when microbes existed but vegetation had not yet appeared. There has been little global reaction because life cannot exert forces on Earth’s atmosphere, hydrosphere and other planetary systems.

- Stage 2 – Mature Biosphere: A characteristic of the Earth, also before technological species, about 2.5 billion to 540 million years ago. Stable continents formed, vegetation and photosynthesis developed, atmospheric oxygen accumulated, and the ozone layer appeared. The biosphere has had a strong impact on the Earth, which may help maintain the Earth’s habitability.

- Stage 3 – Immature technical field: It is now characteristic of the Earth, with interconnected systems of communications, transportation, technology, electricity and computers. However, the technosphere is still immature, as it is not incorporated into other Earth systems, such as the atmosphere. Instead, it derives matter and energy from Earth’s systems in ways that will push the whole into a new state that likely does not include the technical envelope itself. Our current technical field, in the long run, is working against itself.

- Stage 4 – Mature Technical Area: Where the Earth should aim to be in the future, Frank says, is with technological systems in place that benefit the entire planet, including global energy harvesting in forms like solar that doesn’t harm the biosphere. A mature technicalsphere is an ocean that has co-evolved with the biosphere into a form that allows both the technicalsphere and the biosphere to flourish.

“Planets develop through immature and mature stages, and planetary intelligence is indicative of the time when you reach a mature planet,” Frank says. “The million dollar question is what planetary intelligence looks like and what it means for us in practice because we don’t yet know how to transition to a mature technosphere.”

The complex system of planetary intelligence

Although we don’t know exactly how planetary intelligence might manifest itself, the researchers note that a mature technical field involves integrating technological systems with Earth through a network of feedback loops that make up a complex system.

Simply put, a complex system is anything built of smaller parts that interact in such a way that the overall behavior of the system depends entirely on the interaction. That is, the sum is greater than the sum of its parts. Examples of complex systems include forests, the Internet, financial markets, and the human brain.

By its very nature, a complex system has entirely new properties that emerge when the individual pieces interact. It is difficult to discern a human personality, for example, only by examining the neurons in its brain.

This means that it is difficult to predict exactly what characteristics may appear when individuals form a planetary intelligence. However, a system as complex as planetary intelligence, according to the researchers, will have two defining characteristics: it will have emergent behavior and will need to maintain itself.

“The biosphere figured out how to host life on its own billions of years ago by creating systems for circulating nitrogen and transporting carbon,” Frank says. “Now we have to figure out how to get the same kind of self-maintaining properties with Technosphere.”

Searching for extraterrestrial life

Despite some efforts, including a global ban on some chemicals that harm the environment and a move toward using more solar energy, “we don’t have planetary intelligence or a mature technology field yet,” he says. “But the whole purpose of this research is to clarify where we need to go.”

Frank says that asking these questions will not only provide information about the past, present, and future of life on Earth, but will also help in the search for life and civilizations outside our solar system. Frank, for example, is the principal investigator on the . File NASA Tech Fingerprint Research Grant Civilizations on planets orbiting distant stars.

We say the only technological civilizations we may ever see – those we must see anticipation Let’s see – they are the ones who did not kill themselves, which means that they have reached the stage of true planetary intelligence, he says. “This is the power of this line of investigation: It unifies what we need to know to survive the climate crisis with what might happen on any planet where life and intelligence evolve.”

Reference: “Intelligence as a Process on a Planetary Scale” by Adam Frank, David Grinspson and Sarah Walker, Feb 7, 2022 Available here. International Journal of Astrobiology.

DOI: 10.1017/S147355042100029X

“Reader. Infuriatingly humble coffee enthusiast. Future teen idol. Tv nerd. Explorer. Organizer. Twitter aficionado. Evil music fanatic.”