a A long, long time ago—five decades to be exact—America has been plagued by violent intergenerational confrontations, massive street protests, and a smoldering array of social justice movements. Now, half a century later, similar events and dynamics dominate the public debate. So, perhaps, it is poetic that precisely five decades have passed since the song that captured all that cultural upheaval, American Pie, became a smash hit. “It’s a song that spoke for its time,” said Spencer Proffer, who produced a comprehensive new documentary on the song, The Day Music Died. “But it’s workable now.”

In fact, American Pie only gained in fans and expanded in meaning as it hit successive generations and spawned new covers. Over the years, it has been interpreted by artists from Madonna (who created a commercial triumph, if aesthetically limp, in 2000) to Garth Brooks to Jon Bon Jovi to John Mayer. Over the years, journalists have subjected the song to a Talmudic level of scrutiny, while its songwriter, Don McClain, has been dispensing quirks and insights into his intentions. By contrast, the new documentary offers the first line-by-line deconstruction of the song’s lyrics, as well as the most detailed analysis yet of its musical development. “I told Don, ‘It’s time for you to reveal what journalists for 50 years have wanted to know,’” Proffer said. “This movie was a concerted effort to raise the curtain.”

Additionally, it provides an emotional account of the tragic event that MacLean used as a starting point for the larger story he wanted to tell.

The event, which McClain dubbed “the day of the death of music,” broke the pop world at the time and had a formative effect on the songwriter. On a frigid night in 1959, a small plane carrying Buddy Holly, Richie Fallens, and JB Richardson (The Big Popper) crashes into a cornfield in Clear Lake, Iowa, minutes after takeoff, killing everyone on board. The documentary begins with this event, returning to the Surf Ballroom, where the stars played their last show. The filmmakers recorded a coup when they brought before the camera a man who had seen that fateful concert, as well as the man who owned the airline that chartered the ill-fated plane. Furthermore, it features a touching interview with Valence’s sister Connie, whom we see thanking McClain for immortalizing her brother in the song.

The first part of the film covers the beginning of McClain’s life, including his time as a paper boy in the New York City suburb where he grew up. In an extended interview for the film, McClain spoke about the delivery of the newspaper that reported the incident, something he alludes to at the beginning of the song’s lyrics. At that time, Buddy Holly was his musical idol. If his death was instigated by the song’s lyrics, a more personal loss changed the course of McClain’s life. When he was 15 years old, his father died suddenly of a heart attack. “It had a profound effect on him,” Proffer said. “He carried his father’s death in his soul.”

In his grief, MacLean threw himself into music, and developed a talent promising enough to win parties at folk clubs in Greenwich Village as a teenager. He found a role model in The Weavers, particularly in Pete Seeger, with whom he was a friend. The primacy of storytelling in the group’s songs, as well as its social and cultural underpinnings, served as a model for certain aspects of the American pie. From Seeger, he also learned the value of Singalong. One obvious draw of American Pie is the chorus that anyone can copy. The simplicity of her melody echoes children’s music. “It’s like a campfire song,” said Proffer. “Everyone is invited to sing.”

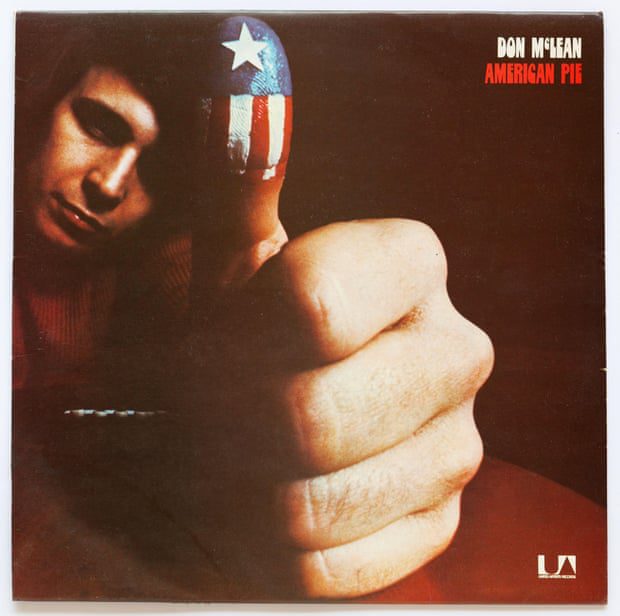

Some of the song’s lyrics are even quotes from nursery rhymes, including “Jack be a nimble / Jack be quick.” The album cover of American Pie emphasized the connection by highlighting McClain’s thumb in the foreground to indicate another nursery song about Little Jack Horner, who “put on his thumb/pulled a leg.”

At the same time, the message of the song cannot be for adults. “For me, American Pie is a eulogy for an unfulfilled dream,” the song’s producer, Ed Freeman, says in the film. We witnessed the death of the American dream.

“The country was in an advanced state of psychological trauma,” McClain says in front of the camera. “All these rallies and riots and burning of cities.”

Most of it made McClain want to creatively shoot the moon. “I wanted to write a song about America, but I didn’t want to write a song about America like anyone had written before,” he says.

This was no small goal given the number of songwriters of the time who were penning their own poems to the disappointment of the American dream. These stories ranged from Paul Simon with American Town (which imagines a nation of freedom sailing at sea) to Dion’s version of Abraham, Martin, and John (which poignantly addressed the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy).

McClain’s desire to stand out from the other singers and songwriters who dominated music at the time also had a career motivator. His debut album, Tapestry, released in 1970, didn’t make any waves, and his small record label MediaArts didn’t have much faith in him. However, the big song he devised to change that arrived in a form that defies the simplest stroke ordinance – lasting no more than three minutes. I picked up American Pie for eight and a half minutes, and it was stuffed with fuzzy, dream-like images of a fever.

In fact, McClain wrote more verses than the last song. “He kept writing,” Proffer said. “If it was more than eight minutes, it would have been 16”

In that sense, he shares something with Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. In both songs, the author wrote the verses and discarded them (although much is abandoned in Cohen’s case). Both songs have also gained prestige and influence over the years. (Coincidentally, Cohen’s song It is also the subject of a new documentary, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, Journey, Song). However, in essence, they are fundamentally different. “Alleluia is a spiritual study,” Proffer said. “American Pie is a social study.”

Often times, he is shy. The words are filled with cryptic references to kings, queens, and stooges, along with a cast of cultural figures that together turn them into a virtual quiz pop: “The name of this reference!” The score made the song particularly involving the listener’s excitement to solving the mystery. “Every time you listen, you think of something else,” Proffer said.

In the film, MacLean rejects some of the most common speculation about his reference points. Elvis was not the king in question. “The Girl Who Sang the Blues” wasn’t Janis Joplin, and Bob Dylan wasn’t the clown. In 2017, Dylan commented on his alleged reference to Rolling Stone: “Joker?” He said. “Sure, the clown writes songs like Masters of War, A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall, it’s okay, Ma.” I must think he’s talking about someone else.”

As fanciful as some of MacLean’s lyrics were, the primary reference to “the day of the death of music” has turned the song into a history lesson for those born too late to remember the event as overwhelmingly as Maclean did. Even when the song debuted, it’s been over a decade since it broke, the equivalent of a thousand years of fast-paced pop life.

One of the documentary’s most interesting sections presents a careful dissection of the evolution of song arrangement. She didn’t find her true groove until they brought in session keyboardist Paul Griffith, who has played on core recordings by everyone from Dylan to Steely Dunn. His piano parts brought an evangelical fervor to the song, as well as an extra pop bounce. Hooks like this helped a song of intimidating intensity and length become loved by millions.

To deal with her height, McLean Records had a clever idea. The first half of the song appeared on the “A” side of the song, while the second part was moved to the “B” side. The result turned side A into a bush that the listener had to see through to the end. Subsequent demand forced AM radio stations to play on both sides. At the same time, FM radio – whose mission was to go deeper and play longer – was reaching its commercial peak at the time. Released at the end of 1971, American Pie hit #1 by January of 72, where it stayed for an entire month. For 39 years, it held the record for the longest song to hit #1 – until Taylor Swift’s 10-minute hit, All Too Well, broke it.

Interestingly, both songs have some anger. But over time, MacLean’s piece has changed considerably in the public consciousness. Today, it’s made and sometimes interpreted, as if it were some kind of exciting sequel to The Star-Spangled Banner. In the movie, one fan describes it as a song that makes you “pause and be grateful for all you have”.

In the film, Garth Brooks says it’s a song “about that drive for independence, the drive for discovery…to believe that anything is possible.”

Both opinions couldn’t be more puzzling, given the overall sadness and disgust with the actual words. Indeed, American Pie ends with “Father, Son and Holy Ghost”, so terrified by the state of the country that they—the so-called saviors of humanity—float and flee to the coast. “People don’t think about what (the song) really means,” Prover said. “They think about what makes them feel.”

If these reactions remove the song’s context too far, the film can recontextualize it. Furthermore, it aims to expand its heritage by showing new versions of the song sung by someone from the current generation (24-year-old British singer Jade Bird) as well as artists from another culture (singer Gincarlos and producer Maffeo, who created a Spanish-language version) . “It’s exciting to know that something that happened 50 years ago can resonate in later generations,” Proffer said. “By listening to the song, people get a glimpse of what life was like back then and what it is like today.”

“Internet geek. Friendly coffee trailblazer. Infuriatingly humble musicaholic. Twitter fan. Devoted alcohol aficionado. Avid thinker.”