The dark reddish-brown stone, picked up from the Sahara Desert in Morocco a few years ago, appears to be an earth rock that was flung into space where it remained for thousands of years before returning home – surprisingly.

If scientists are right about this, the rock will be officially named the first meteorite to bounce off Earth.

It was the discovery team’s work foot last week at an international geochemistry conference and has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

“I think there is no doubt that this is a meteorite,” said Frank Brinker, a geologist at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany who was not involved in the new study. “It is just a matter of debate if it is really from Earth.”

Related: More than 100 space rocks collected by meteorite hunter Jeffrey Notkin are ready to go today

Early diagnostic tests show that the unusual stone has the same chemical composition as igneous rocks on Earth. Interestingly, however, some of her elements seem to have been changed into lighter forms of herself. These lighter releases are only known to occur when interacting with energy cosmic rays in space, which provided one of two major clues announcing the rock’s journey beyond Earth, geoscientists say.

Measured concentrations of these lighter elements, called isotopes, are “too high to be explained by processes occurring on Earth,” said Jérôme Gacheca, a geophysicist at the French National Center for Scientific Research who is leading the investigation of the unusual meteorite, officially named Northwest Africa 13188 (NWA 13188).

Gacheca and his colleagues strongly suspect that the rock was first hurled into space after an asteroid hit Earth nearly 10,000 years ago. The only other natural event capable of hurling rocks to great heights is a volcanic eruption, but geologists say this possibility is unlikely to explain the latest finds. Rock explodes even from records Honga Tonga – Hong Haapei The submarine volcano peaked last year at 36 miles (58 kilometers) — long before the edge of Earth’s atmosphere, the sill the meteor appears to have flown much beyond.

Once catapulted into space past Earth’s protective mantle, NWA 13188 will be vulnerable to the galaxy cosmic rays, made of high-energy particles created by exploding distant stars that traverse our solar system at light-like speeds. Such abundant bands are known to bombard meteorites and leave behind distinct, detectable isotopic signatures such as beryllium-3, helium-10, and neon-21. In NWA 13188, levels of these elements were higher than those found in any rock on Earth, but lower than those found in other meteorites. Scientists say this shows that the rocks of interest may have spent anywhere from 2,000 to a few tens of thousands of years in orbit around the Earth before re-entering its atmosphere.

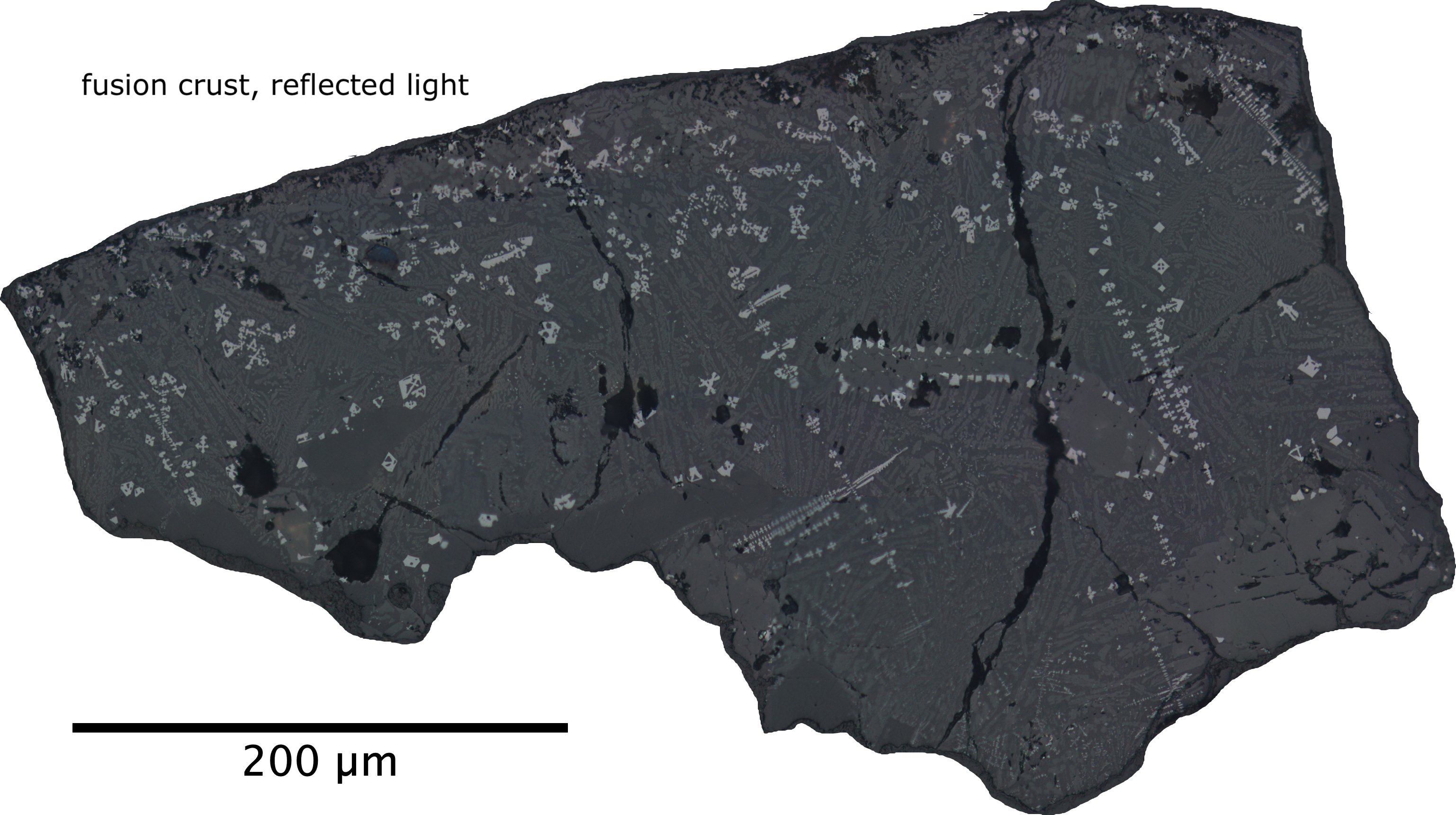

The second crucial piece of evidence revealing the rock’s journey into space is the shiny, molten surface layer called fusion crust, which forms when space rocks race through Earth’s atmosphere on their journey to Earth.

The 1.4-pound NWA 13188 was purchased in 2018 at one of Europe’s largest annual mineral and gemstone fairs in Sainte-Marie-Osse Mines, France, by Albert Gambon, a French professor emeritus from the Sorbonne University in Paris. He said he keeps in touch with meteorite hunters and dealers and has purchased nearly 300 meteorites for his university in the past two decades.

“I bought this just because it was weird,” Gambon said. “No one really knows the value of this stone.”

It is very likely that the Moroccan merchant who sold the meteorite to Jambon bought it from nomadic Bedouin tribes gathering exotic stones in the desert, so it remains a mystery exactly where NWA 13188 landed after it returned to Earth. Two years ago, Jambon teamed up with Gattacceca, a longtime collaborator who catalogs meteorites for private collectors.

The team’s initial analysis of the Boomerang meteorite hasn’t convinced other geologists, because the conclusions reached so far are indisputable that the rock is, in fact, from Earth.

“It’s an interesting rock that deserves further investigation before unusual claims are made,” said Ludovic Ferrier, curator of the rock collection at the Natural History Museum Vienna in Austria, who was not involved in the new study.

The Gattacceca team also did not determine the meteorite’s age, which is a necessary indicator of its origin. The rock has been classified as an unassembled achondrite, and meteorite members of this class have been classified as 4.5 billion years old – the same as the solar system. If NWA 13188 is a terrestrial rock, it must be much younger.

Another concern is the lack of a large impact crater on Earth that is small enough to fit into the proposed timeline. Gacheca and his colleagues estimate that a crater about 12.4 miles (20 km) wide must have formed if an asteroid 0.6 mile (1 km) wide slammed into Earth just 10,000 years ago. Of the 50 known impact craters on Earth that are of the required size, none are younger than millions of years old.

The desert, where NWA 13188 was found, is home to 12 craters, only one of which is 11.1 miles (18 km) wide and at least 120 million years old, according to Earth Impact Database, a repository of confirmed impact craters on Earth. Although there are dozens of potential impact craters on the African continent awaiting verification, critics say a 10,000-year-old crater is impossible to overlook.

“Such an impact crater could certainly have been discovered recently,” said Ferrier, who has found some impact craters including one in Congo. Asteroids transfer their momentum to the Earth where they strike, he said, amplifying local pressures and temperatures to such extremes that Earth’s rocks would melt, and those “inside such a last big crater would still be hot.”

Other outstanding measurements include unequivocal data on how much shock from the original impact the stone absorbed. This unique signature can be detected in the fine, permanently changing structures of the mineral crystals that make up the rock. Estimating meteor shock levels is “something that can be verified or done in an hour or so maximum, using the naked eye,” Ferrier said, “and therefore, an inexpensive and very important observation in this case.”

If detection stops, NWA 13188 will populate a type of bouncing meteor, although there is no official name for such a classification at present. Some geologists call the group “terrestrial meteorites.”

The only confirmed member so far is a small piece of land that once existed etched on the surface of the moon by the Apollo astronauts in 1971.

“Reader. Infuriatingly humble coffee enthusiast. Future teen idol. Tv nerd. Explorer. Organizer. Twitter aficionado. Evil music fanatic.”